Category Archives: India Patent Filing

Can the Indian patent office restrict the examination to certain set of claims?

A patent application is queued for examination once the request for examination has been made in the prescribed manner under sub-section (1) or sub-section (3) of section 11B. During the examination, the Patent office examines the patent application and issues a first examination report (FER), which is communicated to the Applicant. The objection raised in the FER may be with respect to novelty, inventive step, sufficiency of disclosure, formal requirements and unity of invention, among others.

The IPAB on its order dated 27th October 2020, had set aside the impugned order of the respondent (THE CONTROLLER OF PATENTS) against the patent application numbered 531/DELNP/2013 (hereinafter referred to as “the Current application”) and granted a patent to the applicant (UNIVERSITY OF COPENHAGEN). During examination of the current application, Examiner had raised objection that the claims lack unity of invention under section 10(5) and additionally restricted the examination to only a chosen set of claims. Section 10(5) of the Indian patent act mandates that a single patent application should relate to single invention or to a group of inventions linked so as to form a single inventive concept.

Fact of the case

A National phase application numbered 531/DELNP/2013 based on the PCT International application was filed by the applicant. A first examination report (FER) was issued on 02 July, 2018. One of the objections communicated in FER are as follows:

“In view of the plurality of distinct inventions (see Para under heading- Unity of invention), the search and examination u/s 12 and 13 of the Patents Act, 1970 (as amended) has been deferred with respect to groups of inventions II to VII containing claims 22 to 28. Hence, present examination report is restricted to Invention I having claims 1-21 only.”

Further, a hearing was conducted and the Appellant filed written arguments along with amended set of claims at the Patent Office within the stipulated time. An impugned order was issued by the respondent on 06 March, 2020.

IPAB’S DECISION

Therefore, while the objection with regard to ‘unity of invention’ can well be taken if the plurality of invention is found to have been claimed but restricting the examination to any chosen set of claims by the Controller is not mandated by the Patents Act,1970, particularly so when the fee in respect of examination of all the claims are paid by the applicant.

A review of the International Search Report in respect of this application in International Phase, we notice that International Seraching Authority (ISA) has found the lack of “unity of invention” and searched only the first set of claims i.e. claims 1-21. Further, ISA objections on ‘Unity of Invention” are verbatim matching with that raised by the learned Controller in the instant application.

CONCLUSION:

During the examination of the patent application, the search and examination of all the claims has to be carried out irrespective of the fact whether the patent application relates to a plurality of invention. The Controller may raise objection for lack of unity of invention under section 10(5) and instruct the Applicant to elect the set of claims the Applicant desires to retain and subsequently file a divisional application for the other set of claims. However, in practice the Controller restricts the search and examination to chosen set of claims without any intimation to the Applicant. Moreover, the examination report issued should not be a verbatim matching with search report issued by the other patent office as the patent law varies for each jurisdiction. For example, the WIPO conducts a search for only first set of claims, as the ISA (International search Authority) is under no obligation to examine the multiple set of claims once a single fee is paid. They intimate the same to the Applicant and conduct a further search on receipt of the corresponding fee. On the other hand, the India Patent Act and Rules mandates to examine all the claims as the fee for all the claims are paid prior to issuance of the FER and forbids the examination of selected set of claims as per the convenience of the Controller.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Term of a patent in India and Strategies to reap maximum benefits from the patent term

What is a Patent?

In basic terms, Patent is a set of exclusive rights granted by a country to an applicant in exchange for a public disclosure of their invention. The invention could be a product or a method/process which provides a technical solution to a problem or offers a new way of doing something. The “exclusive rights” granted to the applicant that include the rights to exclude others from making using, selling, importing, or distributing the patented invention without the permission of the patentee.

Types of Patent Applications

In India, Patent applications can be broadly classified into 3 types based on the approach taken by an applicant for filing a patent application in India viz.,

- Ordinary application

- Convention application

- PCT National phase application

A much detailed explanation of the types and filing of different types of patents applications in India can be read here.

Term of a Patent

Section 53(1) of The Patents Act 1970 sheds light on the term of patents. Term of patent is a period of time during which the applicant is awarded exclusive rights to exclude others from infringing i.e., making, using, selling, importing, or distributing the patented invention without the permission of the applicant. The set of exclusive rights for a patent is granted to an applicant for a limited period of time, which is 20 years. The patentee will have the exclusive rights to exclude others from making, using, selling, importing, or distributing the patented invention for a period of those 20 years. However, once the term of the patent is completed, the patent is termed expired, implying that the patented invention can now be made, used, sold, imported, or distributed by anyone without needing the permission of the patentee.

During the term of the patent i.e., 20 years (assuming the patent is active), the patentee can have a monopoly in the market over the patented product by stopping others from commercially exploiting the patent or can license the patent to other entities. The patentee can also claim damages from entities that infringe upon the patent, however, can only claim damages for infringements that might have occurred after the date of publication of the application until the expiry of the patent. This is where the term of a patent plays a vital role.

The term of a patent is a fixed 20 year term, however, calculation of start of the term of a patent may change based on the approach of an applicant in filing a patent application in India. Calculation of start of the patent term (considering just the 3 types of applications mentioned in the foregoing) is different in two scenarios, one in case of Ordinary application and one in case of Convention application or PCT National phase application.

Ordinary Application

In case of an Ordinary application, the patent term starts from the earliest priority date. In a scenario where a provisional application is filed followed by a complete application within the 12 months due date, the date of filing the provisional application (one with earliest priority date) is considered for calculating the term of the patent. For example, assuming a provisional application being filed on January 01, 2000 followed by a complete application filed on January 01, 2001. Assuming that a request for early publication was field using Form 9 on January 01, 2001 along with the complete application, the application may be published within 2 weeks from the date of filing the request (January 15, 2001 will be assumed as the date of publication for further explanation). The application may then be prosecuted and may be granted. In the instant case, the term of the patent is considered from the earliest priority date i.e., date of filing the provisional application. The expiry of the instant patent application will be on January 01, 2020.

Now, since the application was published on January 15, 2001, the patentee has the right to claim damages, if any, from entities infringing on the patent from January 15, 2001 until the expiry of the patent.

Convention application/PCT National phase Application

In case of Convention application, an application (provisional/complete) may be first filed in a convention country and then enter India within 12 months from the earliest priority date of the convention application. In this case the date of filing the application in India is considered for calculating the term of the patent. For example, assuming a provisional application being filed on January 01, 2000 in a convention country followed by a complete application in India filed on January 01, 2001. Now, similar to the ordinary application, assuming that a request for early publication was field using Form 9 on January 01, 2001 along with the complete application, the application may be published within 2 weeks from the date of filing the request (January 15, 2001 will be assumed as the date of publication for further explanation). The application may then be prosecuted and may be granted. In the instant case, the term of the patent is considered from the date of filing the application in India i.e., date of filing the complete application in India which is January 01, 2001 in the instant case. Therefore, the expiry of the instant patent application will be on January 01, 2021.

Similarly, in case of PCT National phase Application, a provisional application is filed in any of the PCT member country including India, and then file a PCT application within 12 months from the earliest priority date, the date of filing the PCT application is considered for calculating the term of the patent. For example, assuming a provisional application being filed on January 01, 2000 in any PCT member country followed by a PCT application filed on January 01, 2001 simultaneously entering India on the same date. Now, similar to the ordinary application, assuming that a request for early publication was field using Form 9 on January 01, 2001 along with the complete application, the application may be published within 2 weeks from the date of filing the request (January 15, 2001 will be assumed as the date of publication for further explanation). The term of the patent in this case is considered from the date of filing the PCT application which is January 01, 2001 in the instant case. Therefore, the expiry of the instant patent application will be on January 01, 2021.

In view of the two scenarios explained in the foregoing viz., the Convention application and the PCT National phase application, since the term of the patent expires on January 01, 2021 and not on January 01, 2020 as in case of an Ordinary application, and also that the applications in case of Convention and PCT National phase were published on January 15, 2001, the patentee has the right to claim damages, if any, from entities infringing on the patent from January 15, 2001 until the expiry of the patent, which is January 01, 2021 thereby giving the patentee an extended period of protection (which is almost one year in this case) as compared to the Ordinary application filing route.

Strategies for availing maximum benefits from an Indian patent by an Indian applicant

Strategy 1: Ordinary application

An Indian applicant can directly file a complete application instead of filing a provisional application first, and then request for early publication. In this case the application may be published within two weeks from the date of such request. Now, in case of the patent grant, the term of the patent is calculated from the earliest priority date (i.e., date of filing complete application in this case), and since the application was published within two weeks from the date of filing the complete application, the patentee can claim damages from the date of publication of the application. However, in such cases, the applicant is deprived of the 12 months term between the earliest priority date and the date of filing a complete application, as the applicant now directly files a complete application. The patent, in the instant case, effectively expires 20 years from the earliest priority date.

Strategy 2: PCT National phase

An applicant can benefit the most by utilizing the PCT National phase or the convention route. An Indian applicant can avail the benefits by opting for a PCT application, wherein the applicant can first file a provisional application in India followed by a PCT application within 12 months from the earliest priority date, and simultaneously entering India. In such case, the term of the patent is calculated from the international filing date, and for the purpose of examination, prior arts with priority date falling before the earliest priority date are considered. In this way the applicant can avail the most from the patent.

Having said that, the costs incurred in filing an application via PCT national phase route is higher as compared to that of filing an Ordinary application. However, if the applicant believes that the invention is commercially viable, the applicant can opt for the PCT, as the outcome of having the shift in the term of patent protection can outweigh the costs incurred during the filing of such patent applications. On the contrary, this approach may be a hurdle for individual inventors or small companies that are not financial backed and therefore opting the PCT route may not be affordable.

Strategy 3: Convention route

An Indian applicant can directly file an application in any of the Convention country by requesting permission for foreign filing (Form 25), and then entering India within the 12 months deadline. In the instant case too, as discussed in the foregoing, the term of the patent is calculated from the date of filing the application in India, whereas for the purpose of examination prior arts with priority date falling before the earliest priority date are considered.

In case of PCT or Convention application, the patent expires effectively by a maximum of 21 years from the earliest priority date.

Conclusion

In view of the scenarios discussed, it is clear that the applicant benefits the most by opting a PCT route or a Convention route. In fields especially like pharma, where the competition is fierce and the patents play a vital role, just the approach of filing a patent application makes a significant difference. In the PCT and the Convention route, the term of the patent is shifted by almost a year as the term of patent is calculated from the date of international filing/date of filing in India, thereby giving the applicant an edge over opting Ordinary application filing. Having said that, in case of Ordinary application, if the applicant believes that the invention requires no further development, it is advisable for an applicant to directly file a complete application, followed immediately with a request for early publication to avail maximum benefits from the patent.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Duty of disclosure – Information of foreign applications

Section 8 of the Indian Patents Act relates to furnishing information of foreign applications with the IPO. SECTION 8(1) of the Indian Patent Act mandates an Applicant to file an undertaking at the time of filing a Patent Application in India that the Applicant shall keep updating the Indian Patent office about the correspondence applications filed if any in foreign jurisdictions. Such updates have to be provided in Form 3 (Rule 12 (1)) till the date of grant of the Patent in India. Whereas, information under Sec 8 (2) has to be furnished when the Controller seeks detailed particulars corresponding to the foreign applications at any time during the prosecution of the Indian patent application.

“(1) Where an applicant for a patent under this Act is prosecuting either alone or jointly with any other person an application for a patent in any country outside India in respect of the same or substantially the same invention, or where to his knowledge such an application is being prosecuted by some person through whom he claims or by some person deriving title from him, he shall file along with his application or subsequently within the prescribed period as the Controller may allow—

(a) a statement setting out detailed particulars of such application; and

(b) an undertaking that, up to the date of grant of patent in India, he would keep the Controller informed in writing, from time to time, of detailed particulars as required under clause (a) in respect of every other application relating to the same or substantially the same invention, if any, filed in any country outside India subsequently to the filing of the statement referred to in the aforesaid clause, within the prescribed time.

2) At any time after an application for patent is filed in India and till the grant of a patent or refusal to grant of a patent made thereon, the Controller may also require the applicant to furnish details, as may be prescribed, relating to the processing of the application in a country outside India, and in that event the applicant shall furnish to the Controller information available to him within such period as may be prescribed.”

Timeline to file information under section 8

|

Section 8 (1), Rule 12 (2) |

If the other convention/NP applications were filed before the Indian convention/NP application was filed, the 6-month deadline is calculated from the Indian filing date.

|

If the other convention/NP applications were filed after the Indian convention/NP application was filed, the 6-month deadline is calculated from the date of filing of each corresponding foreign application. |

|

Section 8 (2); Rule 12 (3) |

Within 6 months from the date of communication from the controller seeking such details. |

|

Non-compliance of Sec 8 can be a ground for pre-grant, post-grant opposition and revocation under section 25(1)(h), 25(2)(h) and Sec 64(1)(m), respectively. There has been instances wherein the non-compliance of section 8 information has been used as one of the effective tools to revoke a patent.

|

Ajanta Pharma Limited v. Allergan Inc., Allergan India PVT. LTD

|

Allergan’s patent IN212695 was revoked |

|

Hindustan Unilever Limited's patent by Intellectual Property Appellate Board |

Hindustan Unilever Limited's patent IN 195937 was revoked. |

It shall be noted that the burden of proof lies on the Defendant (infringing the patent) to show that the primafacie case of section 8 has not been met by the Plaintiff. A mere statement without any facts and evidence to support that there has been violation of section 8 cannot be considered to institute a proceeding. In FRESENIUS KABI ONCOLOGY LIMITED V. GLAXO GROUP LIMITED & ANR, the FRESENIUS KABI ONCOLOGY LIMITED V. GLAXO GROUP LIMITED & ANR had failed to file furnish any facts and evidence to support their revocation petition.

Roche Vs Cipla decision: A landmark judgement was passed by the Delhi High Court in Roche Vs Cipla case on 2008 stating that a Patent cannot be revoked solely on the ground of non-compliance of section 8.

156. Consequently, the ground of violation of Section 8 read with Section 64(1)(m) is made out. However, still there lies a discretion to revoke or not to revoke which I have discussed later under the head of relief. Under these circumstances, even in case, the said compliance of Section 64(1)(m) of the Act has not been made by the plaintiffs, still there lies a discretion in the Court not to revoke the patent on the peculiar facts and circumstances of the present case. The said discretion exists by use of the word – may II under Section 64 of the Act. Thus, solely on one ground of non-compliance of Section 8 of the Act by the plaintiffs, the suit patent cannot be revoked”

WILFUL or UNINTENTIONAL SUPRESSION OF FACT

In KONINKLIJKE PHILIPS VS SUKESH BEHL CASE, the Delhi High Court stated that it is important to analyse if there has been suppression of information by the Plaintiff. Moreover, one has to consider if such suppression of fact was wilful or unintentional. Unintentional suppression of facts and information may be considered as one of the grounds to avoid revocation of patent under section 64 (1) (m). In this context, it is worth mentioning “Philips Electronics Vs. Maj (Retd). Sukesh Behl” case.

Philips Electronics sued Maj (Retd). Sukesh Behl, Proprietor of Pearl Engineering company for allegedly infringing Patent: No: 218255 entitled “METHOD OF CONVERTING INFORMATION WORDS TO A MODULATED SIGNAL” on 2012. The defendant filed a revocation petition under section 64 (1)(m) as the patentee or plaintiff failed to comply with Section 8 of the Act. The defendant contented that the plaintiff suppressed the vital information of the foreign applications corresponding to same or substantially same invention filed in India.

As a counter argument, Philips submitted an affidavit stating that additional information was inadvertently missed out by paralegal who failed to photocopy the back side of a document while submitting the application.

Decision of the Delhi High Court:

14. It requires to be noted that while the Plaintiff does not deny that a part of the information concerning the pending foreign applications was inadvertently not disclosed, there is no admission as to the withholding of that information being deliberate or that there was wilful suppression of such information. That surely would be a matter for evidence. Further, the question whether the non-disclosure of the above information contained on the reverse of the first page in the first instance before the COP was material to the grant of the patent raises a triable issue. It is not possible at the present stage for the Court to form a definitive opinion on the above aspects. If at the end of the trial the Court, after examining the evidence, agrees with the Defendants that the information that was withheld was material to the grant of the patent itself, it might proceed to revoke the patent. Alternatively, it might disagree with the Defendant and decline to revoke the patent. In other words, that determination would have to await the conclusion of the trial. For the aforementioned reasons, the Court is of the view that it is not possible to grant the prayer made in this application by the Defendant under Order XII Rule 6 CPC.”

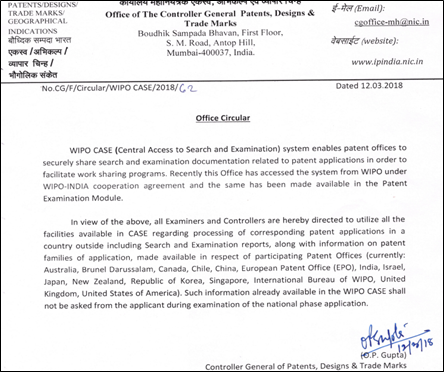

Moreover, recently the Indian patent office has issued a notification instructing the Examiners and Controller’s to utilise the WIPO case system and directed not to ask the Applicant’s about such details during prosecution of the national phase application.

CONCLUSION:

The purpose of inclusion of section 8 in the Indian patent Act is clearly mentioned in the Ayyangar report.

“It would be of advantage therefore if the applicant is required to state whether he has made any application for a patent for the same or substantially the same invention as in India in any foreign country or countries, the objections, if any, raised by the Patent offices of such countries on the ground of novelty or un patentability or otherwise and the amendments directed to be made or actually made to the specification or claims in the foreign country or countries.”

As mentioned in the Ayyangar report produced above, the sole purpose of submission of section 8 information to ease the prosecution of the patent application and help the Patent Examiner to prosecute the Patent application. Submission of Section 8 information is a procedural requirement to be complied by the Applicant till the grant of the patent. Non -compliance of such a procedural irregularity should not result in revocation of a patent that has overcome the hurdles of novelty and inventive step. It has been observed that the Delhi High Court has also stated the same in Roche Vs Cipla case. Further, prior to passing any harsh judgement against a patent, it is advisable to enquire if failure to comply with section 8 is done deliberately or unintentional. With the case law discussed in the preceding paragraphs it is worth mentioning that the jurisprudence with respect to section 8 is evolving. Procedural irregularity should not be considered as one of the tools to revoke a patent. Instead in case of non-compliance of such information, the Applicant should be given an opportunity to furnish such details, failure of complying to this opportunity may be considered to take a decision. Moreover, to avoid any such repercussions it is advisable that the Applicant and the representatives of the Applicant should diligently comply with Section 8, non-compliance of which would be used as an effective tool to invalidate a patent.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

80% Reduction in patent fees for Educational Institutions – A much awaited booster for patenting new Ideas in India

Indian Educational Institutions have been the hub of some of the most innovative minds. An amalgamation of ideas from a student and teacher during a learning process can foster substantial innovation. But one thing that was lacking so far was the affordability to legally own and monetize these ideas by the fraternity in educational institutions.

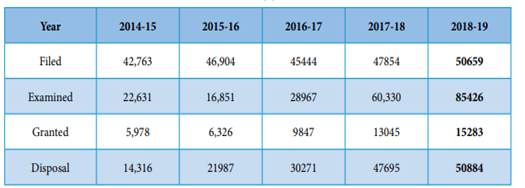

The Annual report of the Indian Patent office for the year 2018-19 indicated that the number of patents filed have steadily increased on a yearly basis as shown below:

Trends in Patent Applications:

Courtesy: Annual Report 2018-19 by Indian Patent Office

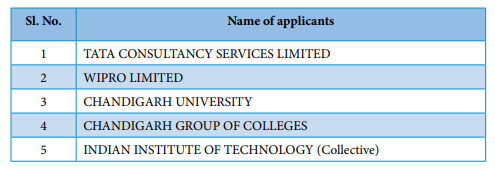

However, when we look at the top 5 Indian applicants for patents, we observe that very few educational institutions make it to the top 5 applicants’ list in India. Also, the number of patents filed by all the educational institutions in India put together is hardly 2% of the total number of patents filed in India.

Top 5 India applicants for patents in the field of Informatioon Technology

Courtesy: Annual Report 2018-19 by Indian Patent Office

Therefore, a rebate of 80% according to the notification published on 21st September 2021, by the Ministry of Commerce and Industry, will now attract more and more projects to be filed and monetized by educational institutions across the nation. In accordance with the notification, the Central Government has made certain rules to amend the Patent Rules, 2003. The amended rules are called Patent (Amendment) Rules, 2021, and has come into force on the date of their publication in the Official Gazette. The key takeaways of the notification are as follows:

|

Sl. No |

Rules |

Sub-Rule |

Inference |

|

1. |

2 |

(ca) “educational institution” means a university established or incorporated by or under Central Act, a Provincial Act, or a State Act, and includes any other educational institution as recognized by an authority designated by the Central Government or the State Government or the Union territories in this regard; |

All the universities and other educational institutions recognized by any one of the Central Government, State Government or Union Territories will hence forth be recognized as “educational institution” by the Indian Patent Office for categorizing under the right fee slab. |

|

2. |

7 |

(1) Provided further that in the case of a small entity, or startup, or educational institution, every document for which a fee has been specified shall be accompanied by Form-28. |

The filing fee for educational institution is same as the filing fee for a natural person, small entity or a startup. |

|

|

|

(3) In case an application processed by a natural person, startup, small entity or educational institution is fully or partly transferred to a person other than a natural person, startup, small entity or educational institution, the difference, if any, in the scale of fees between the fees charged from the natural person, startup, small entity or educational institution and the fees chargeable from the person other than a natural person, startup, small entity or educational institution, shall be paid by the new applicant along with the request for transfer. |

In case the educational institution chooses to transfer their processed application to any entity other than a natural person, small entity or a startup, the difference in the chargeable fees must be paid by the new applicant. |

|

3. |

First Schedule |

Headings and sub-headings in Table 1. |

“educational institution” is included in the heading and sub-heading of Table 1 along with natural person, small entity and a startup. |

|

4. |

Second Schedule |

Form 28 |

“educational institution” is included in Form 28 along with natural person, small entity and a startup. |

Who will qualify as an educational institution?

In accordance with the newly amended Rule (2) (ca), for an Indian applicant, an “educational institution” is a university established or incorporated by or under Central Act, a Provincial Act, or a State Act. Further, any other educational institution recognised by an authority designated by the Central Government or the State Government or the Union territories will also be recognised as an educational institution in India. A foreign applicant can qualify as an educational institution by furnishing any legal document to ascertain the same.

How can an educational institution claim the benefits of educational institutions?

In accordance with the newly amended Rule (7), the educational institutions are recognized on par with a small entity or a startup and are therefore entitled to file the required documents using the new Form -28. Further, the scale of fees chargeable for an educational institution is on par with a small entity or a start-up.

CONCLUSION

Most of the educational institutions take a minimum of 10 years to establish themselves. Their profits do not alter according to the industrial requirements. Therefore, recognizing them on par with a small entity thereby reducing the filing fees by 80%, will make it easy for young innovators to legally protect their innovations.

Further, the provision of 80% rebate for filing patents by educational institutions seems like a win – win opportunity for both the government as well as the educational institutions. On one hand, by reducing the filing cost for patents filed by educational institutions, the Government has channelized the innovative ideas towards strengthening the Indian Economy. On the other hand, a greater number of educational institutions will now be willing to file patents of innovative projects carried out by students under the guidance of their respective mentors. This in turn will provide an added income to the educational institutions once the patents are monetized.

Moving in this direction, the Andhra University has welcomed the new rule by setting up an exclusive centre for Intellectual Property (IP) within its campus. The IP centre will henceforth oversee the documentation process and bear the cost of filing for IP rights of researchers in Andhra University. On the whole, this new rule has set a platform to utilize the vibrant young minds towards building a strong economy thereby contributing to the growth of the nation.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Post – Dating of a Patent Application – Indian Perspective

Section 17 and 9(4) of the Indian Patent Act deals with post-dating of a patent application. It shall be noted that only a complete application can be post-dated to a later date. To interpret the provisions of post -dating an application, one has to rely on the Judgement passed by Delhi High Court on MAY 26, 1999 in Standipack Private Limited & … vs M/S. Oswal Trading Co. Ltd.

The Judgement recites:

“8. The aforesaid provisions make it crystal clear that post-dating of the patent can be done only to the date of filing of the complete specifications. In the present case the Controller of Patents had filed the original records relating to the grant of patent in favour of the plaintiff. The said records reveal that the application for the grant of patent was originally filed by plaintiff on 11.4.1989 and the complete specification was filed on 11.10.1990. The Controller of Patents however, post-dated the patent to 11.7.1989 although complete specifications followed by the provisional specification was filed on 11.10.1990. Thus the post-dating of the patent by the Controller to 11.7.1989 prima facie appears to be in violation of the provisions of Section 9 of the Act. The date of the patent, therefore, should have been 11.10.1990. The patent documents referred the validity of the patent for 14 years from 11.7.1990. Thus the validity of the patent has also been ignored by the Controller of Patents. The plaintiff also during the course of arguments admitted that complete specifications were submitted on 11.10.1990, which is the date from which the Patent granted would be effective. Thus post-dating the Patent to 11.7.1989 appears to be illegal in view of the provisions of Section 9(4) of the Patent Act and the provisions of Section 17 are subject to Section 9.”

Further, section 9 (4) of the Indian patent act clearly mentions the type of application that can be post-dated which are as follows:

- A complete application filed within twelve months in pursuance of a provisional specification filed under section 9(1) and

- A complete specification filed in pursuance of section 9(3). Section 9(3) recites that a complete specification that has been filed can be converted to a provisional specification within twelve months from the date of such filing on requesting the Controller to treat the complete specification as provisional specification, provided the complete specification not being a convention application or a PCT application. In other words, the complete specification must be an ordinary application for the provision of section 9 (3).

How long an application for patent be post-dated?

An application for a patent can be post -dated only to six months from the date of filing of the complete specification. No application can be post- dated to a date later than six months from the date of such filing (Section 17).

Section 17 should not lead to violation of the provisions section 9

Section 17 can be implemented only when the provisions of section 9 are met. This implies that post-dating does not shift the filing date of the complete specification more than 12 months as required under section 9 (1). The complete specification accompanied by the provisional specification has to be filed with the twelve months from the date of filing of the provisional specification.

In this context, a brief summary and decision of the Controller w.r.t 1064/DEL/2010 is discussed herewith for better clarity.

Fact of the case:

|

Application type |

Filing date |

Controller Decision |

|

Provisional application |

06 May, 2010, |

Refused Date: 31/03/2016 |

|

Complete application |

08 August, 2011 |

|

|

Request to post date of the provisional application from 06/05/2010 to 06/08/2010 |

05 May, 2011. |

In the present case, the Applicant had filed a request to post -date the provisional application on 05, May 2011 and subsequently filed the complete specification within twelve months from the new priority date i.e., 06/08/2010. Thus, extending the prescribed time limit of filing of complete specification to 08/08/2011 lead to violation of the provisions of section 9 of the Act.

Decision of the Controller recites,

“In view of above, complete specifications followed by the provisional specification was filed on 08/08/2011, while according to section 9(1), a complete specification shall be filed within twelve month from the date of application, which is 06/05/2010. There is GAP, which could not be filled by filing request for postdating of provisional application, which could be filed anytime before the grant of Page 3 of 3 patent, leading to abandonment of application under section 9(1) of The Patents Act, 1970, and revival of application by postdating of provisional application is against Law of Nature, as once anything treated as deemed to be abandoned, cannot be reconstituted/revived. There is GAP, but, present invention could motivate more innovation and could give momentum to WHEEL OF INVENTION, having potential of industrial applicability, if any. Thus, complete specification has not been filed within the prescribed time period according to section 9(1)of The Patents Act, 1970, and accordingly the application is hereby treated as deemed to have been abandoned according to section 9(1)of The Patents Act 1970.”

Fees and Form

An applicant can file a request to post-date the complete specification by filing Form 30 and paying the prescribed fee. The request to post-date an application can be filed any time before the grant of the patent application.

Fee for filing a request to post -date a patent application:

|

Application |

Form |

For e-filing |

Physical Filing |

||

|

Natural person, start up, small entity or eligible educational institution |

Others, alone or with natural person, start up, small entity or eligible educational institution |

Natural person, start up, small entity or eligible educational institution |

Others, alone or with natural person, start up, small entity or eligible educational institution |

||

|

Post – dating an application |

Form 30 |

|

|

|

|

Examination of post – dated application:

|

Post-dating request made before examination |

Post-dating request made after examination |

|

The examination of the post-dated application is conducted considering the post- dated date as the priority date of the application. |

A fresh examination considering the post-dated date is carried, when a request to post-date, an application is made after the issuance of First Examination Report. |

Timeline to file a post- dated convention application in India

Section 136 (3) of the Indian Patent Act states that a convention application cannot be post-dated under Section 17 (1) to a later date. This implies that the convention application should be filed within twelve months from the date of the first application.

CONCLUSION:

Shifting the priority date to a new date bear the risk of including more number of prior art references with respect to the claimed invention. Additionally, one has to take utmost care to avoid violation of section 9, while applying for post-dating of a patent application as it may lead to refusal of the patent application. Therefore, one has to analyse the repercussions of the post dating a patent application before opting for such provision.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

A note on foreign filing license requirement in India

Foreign filing license (FFL) is mandatory for person(s), who are resident of India, to apply for patents outside India without first applying in India. The guidelines for same are presented in Section 39 in The Patents Act, 1970. The provision states that a person (Applicant or Inventor) who is a resident of India has to request for an FFL in India if he/she wishes to file a patent outside India without first applying in India. Typically, the Applicants resort to applying for patents directly outside India when the invention does not have a commercial value in the Indian market, or the invention is being considered as a non-patentable subject matter in India. In such cases, a written permission has to be sought from the Indian Patent Office (IPO) for applying for patents outside India.

Section 39 of the Patents Act, 1970 reads:

“Residents not to apply for patents outside India without prior permission

(1) No person resident in India shall, except under the authority of a written permit sought in the manner prescribed and granted by or on behalf of the Controller, make or cause to be made any application outside India for the grant of a patent for an invention unless—

(a) an application for a patent for the same invention has been made in India, not less than six weeks before the application outside India; and

(b) either no direction has been given under sub-section (1) of section 35 in relation to the application in India, or all such directions have been revoked.

(2) The Controller shall dispose of every such application within such period as may be prescribed:

Provided that if the invention is relevant for defense purpose or atomic energy, the Controller shall not grant permit without the prior consent of the Central Government.

(3) This section shall not apply in relation to an invention for which an application for protection has first been filed in a country outside India by a person resident outside India.”

Above mentioned Section 39 applies to the residents of India. It shall be noted that the residential status of the applicant(s)/inventor(s) is considered and not the nationality of the person(s). However, since the term ‘resident’ is not defined in the Patents Act, 1970, we rely upon Section 6 of the Income-tax Act 1961-2017 for defining ‘resident’.

According to Section 6 of the Income-tax Act 1961-2017, an individual is said to be a resident of India:

- Is in India in that year for a period amounting in all to one hundred and eighty-two days or more; or

- Is in India for a period of at least 60 days during the relevant year and at least 365 days during the four years preceding that previous year.

The primary motive behind the foreign filing license requirement is to strengthen the national security. Many defense organizations of the government of India have deemed a few technologies important for military purposes and/or potentially detrimental to the national security if exported. Examples of such technologies may include biological warfare agents, explosives so on and so forth. By receiving a FFL from the IPO, the person(s) ensures that the patent application does not belong to any sensitive matter related to defense or atomic energy.

If the IPO deems the subject matter of the patent application to be sensitive and may endanger the national security of India, the FFL may be denied by the IPO. Many a times, to avoid complications of filing a request or the waiting period, people directly file in the foreign country. What the person(s) needs to understand is that as per the Indian Patents Act, it is mandatory for Indian residents to obtain the FFL to file the patent application outside India and when failed to meet such requirements, as per Sections 40 and 118 of the Patents Act, the person(s) may be punishable with imprisonment for a term which may extend to two years, or with fine, or with both. Also, the person(s) may face a risk of rejection of subsequent Indian applications.

However, if the person(s) who is a resident of India has filed a patent application in India, then after six weeks from the date of filling of the patent application, the person(s) is allowed to file the same patent application outside India without requiring a written permission from the IPO. The person(s) also need to ensure no secrecy direction has been issued by the IPO for the submitted patent application.

To file for a FFL, Form 25 (Application for permission for filling the patent application outside India) along with complete disclosure of the invention with the reason for submitting such application has to submitted to the India Patent Office.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Patenting nanotechnology inventions – An Indian milieu

The current Indian patent regime fulfils nearly all the requirements of the TRIPS mandate as well as the Patent Cooperation Treaty, 1970. As newer technologies emerge, Science throws challenges after challenges in the path of law. Protection of some of these technologies has grey areas in Indian Patent system. One such technology is “nanotechnology”. Nanotechnology delas with manipulation of nano-metre scale materials. Nanomaterials being building blocks, can be manipulated to create complex materials and devices by regulating shape and size at the “nanoscale”. The broad term “nanotechnology” encapsulates any scientific area or a combination of areas of biology, physics or chemistry, that deals with the manipulation of materials at nanoscale. The significance of nanotechnology is that materials reduced to the nanoscale show very different properties compared to what they show on a macroscale.

Issues faced by Indian’s patent regime:

One of the major concerns with the nanotechnology inventions is it being multi-disciplinary in nature. Such a multi-disciplinary nature of nanotechnology inventions poses challenges for both the patent offices and courts in determining the patentability of nanotechnology inventions. They are faced with the issues of determining which context is appropriate across many disciplines and industries and include all of them in decision making. Additionally, a potential patentee as well as patent office are required to search for prior art not limited to one field but in wide variety of fields.

Another major concern with the multi-disciplinary nature of the nanotechnology inventions is that the corresponding patents bear overly broad claims. In scenario like this, the patentee tries to maximize the profit by preferring patent claims which could cover as many applications and potential markets as possible. Due to presence of high number of such patents with broad and overlapping claims, possibility of fragmentation of patent landscape and patent thickets arises. The broad definition of nanotechnology creates difficulties for both the inventor and the patent examiner in classifying new inventions for patent office purposes. For instance, a patent application may use broad terms, such as “microscale” or “quantum dot” to describe a nanotechnology invention or may use terms like “nano-second”, thereby covering multiple fields. Lack of a standardized terminology for nanotechnology leads to patent overlapping and broad claiming, and due to which both the inventor and the examiner are required to take considerable caution in order to search for prior art in the area, since “nano” alone is not adequate term to search.

According to the Article 27(1) of TRIPS, a valid and enforceable patent can only be obtained on a certain invention if the claims are novel, non-obvious over the prior art and have industrial usage. However, patenting of nanotechnological inventions is not same as that of other technologies and how to contemplate a certain “invention” differs from country to country. In India, under section 2(1)(j) of the Patent Act, 2005, defines an “inventive step” as a feature of an invention that includes “technical advancement” as compared to the existing knowledge that makes the invention non-obvious to person skilled in the art. These provisions were later made stringent by post amendment in 2005, inclusion of Section 3(b) and 3(d) has posed challenges for new technologies in India. Section 3(b) of Indian patent act forms a barrier to nanobiotechnology based patenting due to assumptions about nanotoxicity caused by nanoparticles. Nano biotech inventions causes environmental damage and due to high permeation ability of the nanoparticles further the nanoparticles may get into the bodies of the humans and may result in nanotoxicity. In addition, according to section 3(d), there is vagueness in particle size to be considered patentable subject matter or not. The word “nano” covers inventions of 100nm in size or smaller. In many cases, the nano material may be combination of many particles or technologies or nano particle of an existing material, without substantial difference in character and industrial application. The invention may not pass the “standard efficacy” requirement demanded by Section 3(d). There is a lack of standard for determination of the efficacy and qualification of enhancement of efficacy in India. However, Section 3(d) could be important means to prevent frivolous grant of patents.

Conclusion:

At present, Indian Patent Act has no provision, and no guidelines or regulations has been framed with respect to regulating this technology through TRIPS agreement which in fact encourages protection of intellectual property across all fields of science. This gap between the technology and the patenting of the technology could be attributed to the lack of awareness about the traits and understanding of the technology.

One of the possible solutions to the problem of patenting nanotechnology inventions can be addressed by bringing amendments in the Indian Patent Act. The lawmakers must devise a mechanism to recognize the field of nanotechnology and formulate a comprehensive plan that deals with nanotechnology and patenting of nanotechnology inventions. Since, nanotechnology covers multiple scientific fields, setting up multiple inspections by a team of examiners from different fields instead of a single examiner would aid in better understanding of the claims. Further, a separate database similar to that of traditional knowledge database could be created for nanotechnology. A policy decision is needed for a separate classification for nanotechnology patents. These preliminary steps would surely encourage the research and innovation in the field of nanotechnology which in turn would render prosperity to Indian patenting system.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Compulsory licensing – a panacea for controlling covid-19?

The on-going Covid-19 pandemic has taken a massive toll on the healthcare sector. The situation is dire in India with has led the Supreme Court of India to declare the second wave as a national emergency. In addition to the rampant increase in COVID cases, the non-availability of medicines such as Remdesivir, Tocilizumab and Favipiravir at sufficient quantities has exacerbated the situation. One of the reasons for lack of affordability and availability of these drugs is that such drugs are patent protected, which provides monopoly rights to the patent owner. In such scenarios, compulsory licensing can play a pivotal role in increasing the availability of the patented drugs.

What is Compulsory licensing?

Compulsory licensing refers to licensing of a patented invention by the government to a third party without the authorization or consent of a patent holder.

|

PROS |

CONS |

|

The patented drug is easily made available to the public. |

The royalty paid to the innovative company may be lesser than the expense incurred in the research and development of the drug. |

|

The patented drug will be available to the public at cheaper price. |

Deterrent to innovation as the monopoly of the patentee over the patent is suspended. |

Compulsory licensing is not a new concept, it is widely recognized in both international and national domains. Paragraph 5 of the Doha declaration and Article 31 of the TRIPS Agreement sets forth a number of conditions for the granting of compulsory licences.

The Indian Patents Act vests special power on the central government u/s 92, under which the central government can invoke compulsory licensing under certain circumstances such as a) national emergency or b) extreme urgency c) public non-commercial use. Section 100 of the Indian Patent Act also empowers the Central Government and any person authorised in writing may use the patented invention for the purpose of the government. The Patent Act also empowers the government to acquire the invention for which an application for patent has been filed or a patent has been granted for public purpose (u/s102). The intention behind vesting such powers on the government is to safeguard public life.

On 20th April 2021, the Supreme Court of India has declared the crisis triggered by the second wave of the Coronavirus as “national emergency”. The Supreme Court has also asked the Central government to consider invoking powers vested under section 92, to hoist the availability of COVID -19 related drugs. Even the Delhi High court has directed the Central government amidst of national emergency to utilise the power vested on the government under section 92 of the Indian Patent Act. Then, why is the government not invoking compulsory license? Considering the on-going pandemic, the need of the hour is to invoke compulsory licensing to combat the deadliest effect of the virus. Every minute, hundreds of people are losing their lives, due to non-availability of the drugs that are useful to treat the infection. It is not the first time that the India is enacting the provision of compulsory licensing. Previously, a compulsory license was granted to NATCO (here) to produce and market Nexavar, an anticancer drug on which Bayer’s holds a patent. The grant of the compulsory license to NATCO clarifies that India is not a new player in this field.

Moreover, the inclusion of compulsory licensing in the Indian patent regime clearly states that when such a pandemic situation arises and the government has to decide whether to preserve the rights of the patentee or give priority to public life, the government has to prioritise public life over the rights of the patentee. The inclusion of such provision in the Patent act is not to exploit the patent rights of a patentee, but to safeguard the public interest and life, as the sole aim of the issuance of compulsory licensee is to address the public health problems. Even the Doha declaration (Paragraphs 4 – 6) on TRIPS agreement and Public health affirmed the flexibility of TRIPS member states in circumventing patent rights for easy access of the medicines or drugs to the public, by invoking compulsory license. Further, compulsory license invoked under such circumstances is provided only for certain periods that is to say -till the national urgency or extreme urgency ceases to occur. The government also pays royalty to the patent holder on usage of the technology invented by the patentee.

Compulsory licensing may not be the panacea for the ongoing crisis. Compulsory licensing of the drugs used to treat COVID may aid in increasing the production of the drugs by third party entities. It shall be noted that a company from Bangladesh produced the world’s first generic Remdesivir without obtaining a license from the patentee Gilead sciences. On the other hand, compulsory licensing may not be effective in the case of vaccines. Typically, pharmaceutical companies protect vaccines using a combination of trade secrets and patents. Therefore, obtaining a compulsory license is not enough for a third-party entity to produce vaccines as some of the crucial information related to the production of vaccines may be protected as trade secrets. Compulsory license is a good step but is not the only step. The government should bring together the stakeholders and device a strategy to address the hindrances to the production of vaccines by third party entities without drastically affecting the interests of the patentee.

We hope this article was a useful read.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Curtains for the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) – End of a possible game changer?

The Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) was established by the Indian Government as an Appellate body on 15th of September 2003 for hearing and resolving appeals against registrar under the Indian Trademarks Act, 1999 and the Indian Geographical Indications of Goods Act, 1999. Later on, from the 2nd of April 2007, IPAB was further authorized to hear and resolve appeals for the orders and decisions made by the Patent Controller under the Patents Act, thereby transferring the powers of High court under the Patents Act and the Copyright Board. With this, the cases relating to patents pending before the High Court were transferred to IPAB.

The idea of having an Appellate Board appeared to lessen the burden of the High Courts. However, the orders passed by the IPAB could be challenged before the High Courts, and then the Supreme Court in cases where High Court orders had to be challenged leading to a very exhaustive prosecution process. To alleviate this, on December 06, 2019, the Ministry of Commerce and Industry in its press release stated that “The applicants of all Intellectual Property Rights (IPRs) can directly file Special Leave Petition (SLP) before the Hon’ble Supreme Court against any order of Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB)” implying that the appeals against the IPAB orders could be directly filed before the Supreme Court. This meant that the appeals could now be directly filed in the Supreme Court against orders from the IPAB, without first approaching the High Court. The Ministry of Commerce and Industry was in favor of the IPAB and affirmed the importance of IPAB with the press release.

IPAB, since its inception has been greatly criticized because of its underworking. Several reasons that have plagued the working of the IPAB have been constant, the reasons being delay in appointment of members and Chairpersons to the IPAB, questions as to their technical qualifications and pending of appointments with regard to technical members, which led to delay in disposing cases. This lack of basic infrastructure and lack of technical appointments to the IPAB added to the concerns of IPAB, which in recent years were resolved to an extent.

The inefficiency of the IPAB led to majority of stakeholders, including a former chairperson of the IPAB, Justice Prabha Sridevan favoring its shutting down. Recently, the Union Finance Minister introduced a draft bill in the Lok Sabha with the proposal of shutting down IPAB and transferring the powers of IPAB back to the High Courts, following which on the 4th of April 2021, The President of India promulgated the Tribunal Reforms Ordinance thereby putting an end to the IPAB.

With the promulgation of the Tribunal Reforms Ordinance, certain appellate bodies were shut down and their functions were transferred to existing judicial bodies. With the shutting down of the IPAB, the cases would now be transferred back to the High Courts, which are already overburdened with the pending civil cases. It is to be noted that the High Courts have more than 55 lakh pending cases as of April 2021. In addition, even the High Courts are operating underpowered with more than 400 vacancies for the Judges to be filled. Bringing patents under the regular court system may result in prolonged litigation which would hamper the patent rights, given the limited period of monopoly for patents, further it would also over-burden the High Courts. This problem is not faced by the likes of trademarks and copyrights, where in the former registration may be prolonged continuously, while in the latter the scope of protection is sufficiently longer to accommodate litigation. One of the other reasons that was given for shutting down of the IPAB was the economics, as a lot of funding was spent on the IPAB over its lifetime as opposed to its generation of limited revenue, considering which shutting down of the IPAB seemed more appropriate.

It shall be noted that each bench of IPAB included a Technical member along with a Judicial member as per section 116 of the Patents Act, who would be a vital player in patent hearings, which is currently missing in the case of High Courts. The Judges appointed in the High Courts mainly hold a degree in Law and have little exposure in the field of science, thereby demanding an additional technical member during hearing of the patent appeals. An additional requirement implies hiring of new technical members fulfilling the requirements of the High Courts for hearing patent appeals, which would basically contradict the very reason provided for disposing the IPAB in the first place. With the shutting down of the IPAB, we need to see how the transfer of cases and their proceedings are carried out and also on how things pan out in the future.

With the increase in IPR awareness and proposed policy changes to promote IPR, one can expect a substantial increase in filings, examinations, appeals and so on. Given this, a fully functional IPAB would have helped in expediting matters related to not just Patents, but also Copyrights, Trademarks and Geographical Indications. Overlooking the shortcomings of the IPAB till date, if the IPAB was to be endowed with most of its requirements for its full functionality, could the IPAB play a major role in the field of Intellectual Property, especially patents? The abolishment of the IPAB at a time when there is an increased interest in Intellectual Property Rights may not be a wise decision. It is a view of majority of stakeholders that the IPAB be reinstated which would in turn aid in uplifting India’s IP landscape, in an era where Intellectual Property rights is given utmost importance.

We hope this article was a useful read.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

Proof of Right requirements for PCT national phase applications

According to Section 6 of the Patents Act, an application for a patent can be made by a true and first inventor, an assignee of the inventor, or a legal representative of any deceased person who immediately before his death was entitled to make such an application. Further, in cases, where an application is made by an assignee of the true and first inventor, according to Section 7(2) of the Act, the applicant is required to furnish a “proof of right” within six months from the date of filing. In case of a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) national phase application, a separate proof of right document need not be submitted in India, provided a declaration under PCT Rule 4.17(ii) had been submitted before the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). This was reaffirmed by the IPAB in its order dated October 27, 2020.

Facts of the case

The Appellant Dow AgroSciences LLC, referred to as DOW hereinafter, filed a PCT national phase application 8373/DELNP/2014 on Oct 08, 2014. It shall be noted that, during the filing of the national phase application, the Appellant submitted the PCT document – PCT Declaration under Rule 4.17(ii) supporting the ‘Applicant’s entitlement to apply for or be granted a patent’, thereby complying with the proof of right requirement. However, in the first examination report (FER) dated June 20, 2018, the Respondent (Patent office) raised an objection that proof of right has not yet been filed according to Section 7(2) of the Act. The Appellant responded by pointing out that a declaration under Rule 4.17(ii) has been filed in place of proof of right.

Despite this submission, the Respondent raised the same objection in the hearing notice. Once again the Appellant responded by pointing out Rule 51bis 2(ii) of PCT guidelines which states that “a designated office shall not require any document/evidence for applicant’s entitlement to apply for Patent, if declaration under Rule 4.17 (ii) is complied with PCT request, unless, it may reasonably doubt the veracity of the declaration, it is humbly submitted that the said declaration should be sufficient and no further evidence/document may be required of the applicant in this context.”

The Respondent, on Jan 30, 2020 issued a decision rejecting the application on the ground of non-filing of proof of right. In the decision, the Respondent cited an earlier order passed by IPAB in NTT DoCoMo Inc. v Controller of Patents and Designs to support the decision. Further, the Appellant made an appeal with the IPAB under Section 117A of the Act against the decision of the Respondent.

Findings and Inferences

The IPAB after examining the appeal, listening to the arguments and analyzing the facts and rules set forth in the PCT treaty and Indian Patents Act, pointed out that the case (NTT DoCoMo Inc. v Controller of Patents and Designs) under reference was based on different facts. The petitioner therein had contention that they had preferred a conventional application which is governed by section 135 of the Patents Act, 1970 and as per section 135, it is clear that section 6 is applicable only to ordinary application and not to conventional applications. Further, the board pointed out that no indication was available to suggest that the Respondent at any point of time had shown a reasonable doubt on the veracity of the indications or declaration concerned. There was no objection on its format either. In case of any doubt on veracity of the declaration, the Respondent could have required any further document or evidence to substantiate the contention of the appellant, in accordance with Rule 51bis.2 of the Regulations under Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) but no such finding were available on records. While stating that the Respondent did not take into account the comprehensive look on the legally accepted norms by which the requirements of filing proof of right could be satisfied, it showed utter obstinateness on the part of the Respondent. Upon making these observations, the board set aside the decision issued by the Respondent and directed the Respondent to grant the patent to the Appellant.

There are few key takeaways from the order issued by the IPAB. Firstly, it is clear from the order that the furnishing of PCT declaration under Rule 4.17(ii) for a PCT national constitutes to proof of right. Therefore, for PCT national phase applications there is no need to submit the proof of right as the declaration under Rule 4.17(ii) would suffice. This negates the need of additional documentation work involved in preparing and filing the proof of right. Secondly, the order also provides a clear cut guidelines to the patent office that if the patent office has reasonable doubt on the veracity of the indications or declaration, it may raise it with the applicant and may further ask the applicant to provide any document or evidence to refute the patent office’s contention. This observation provides the applicant a chance to make necessary submissions to counter the patent office’s contention.

Conclusion

The important thing to be noted here is that, the applicant shall submit a PCT declaration under Rule 4(ii) and need not submit a proof of right only in cases where the assignee and the inventor in the national phase application is same as that in the international application. In a situation where there is a change in the assignee or the inventor after filing the international application and before filing the national phase application, a notification issued by the International Bureau through Form PCT/IB/306 denoting the change in the assignee or the inventor, a form requesting change in the applicant of the national phase application, and a separate proof of right shall be submitted to the patent office. Further, in a situation where the International Bureau has not issued a notification issued by the International Bureau through Form PCT/IB/306 denoting the change in the assignee or the inventor, the applicant should file the national phase application in the name of original assignee and later should submit a form requesting change in the applicant of the national phase application and a separate proof of right.

We hope this article was a useful read.

Please feel free check our services page to find out if we can cater to your requirements. You can also contact us to explore the option of working together.

Best regards – Team InvnTree

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License

- 1

- 2

- 3

- …

- 7

- Next Page »

Subscribe to articles for Free!

Follow

Follow